I’m a member of a Meetup group that is exploring various aspects of a non-hierarchical, self-organized approach to creating and operating business and other organizations, that is casually known as Teal, and is based on the book Reinventing Organizations.

At our latest meeting, Stuart Ramsing led us through a process he uses with some of his clients that he referred to as “Worst Possible Outcomes / Best Possible Outcomes”. My understanding of it is as follows:

- We are evolutionarily hard-wired in stressful situations to jump immediately to imagining Worst Possible Outcomes. When we see something coiled and green in the grass, our initial response is “snake — jump away”. This harks back to our primeval fight/flight/freeze instinct.

- In most modern organizational contexts, this instinctive response is dysfunctional. It leads us to be preoccupied with avoidance, or denial, and to take an adversarial, risk-averse, knee-jerk approach to dealing with distressing situations. It shuts down our creativity. It creates unhelpful tension and anxiety. It prompts us to prefer evasive action, confrontation or inaction, rather than creative or constructive actions.

- A better approach starts with the Worst Possible Outcome (getting it out on the table, also called “daylighting” it, since we’re immediately thinking about it anyway), airing this potential outcome to acknowledge and defuse the anxiety and other negative emotions it creates, and assessing its likelihood objectively and dispassionately. That generally leads to an openness to consider that other, more preferable outcomes are possible, more likely, and attainable.

- The next step then is to imagine the Best Possible Outcome. This isn’t daydreaming about a probably unachievable ideal outcome, begging the question of how it could be achieved. It’s appealing to the innate story-teller in each of us, and co-creating a story that leads to the best achievable result.

- Usually the best means to create this story is iteratively, with a diverse team taking turns adding to and refining the story until it has buy-in from all — it becomes a collective story and implicitly creates a sense of shared purpose and intention. This must be an appreciative, rather than analytical process — as with improvisation, it entails adding “yes, and” statements instead of “yes, but” statements. The objective is not to deny important impediments to the Best Possible Outcome, but to set them aside in pursuit of the achievability of the shared Best Possible Outcome. This acknowledges that the human mind is extremely capable of finding workarounds for obstacles once the goal (intended outcome) is clear. If the collective group can’t find the workarounds and other creative means to achieve the Best Possible Outcome and render the unspoken “buts” moot, then it isn’t the Best Possible Outcome, and the group will naturally tend (and will need to be encouraged) to refine the story until it actually is the Best Possible Outcome, in the consensus view of the group.

- A key success factor in making this work is ensuring the sponsor/facilitator has invited, and that all participants are listening attentively to, all the voices that can add value — those that bring as complete as possible knowledge of the situation, and a diversity of perspectives and ideas.

- Once the story is complete, an important part of the learning is a bit of self-learning: assessing how you personally feel about the collectively-determined Best Possible Outcome (eg proud of the group, surprised, energized, relieved), contrasted with the instinctive negative feelings (anxiety, fear, distress, anger, hopelessness, dread, shame, defensiveness etc) that you noticed immediately arose when the Worst Possible Outcome was contemplated.

It takes a certain degree of discipline (and a good facilitator) to prevent several things from happening that could sabotage the process: groupthink (it’s easier to give a nod to something that’s safe and promising, than to improve the story with more daring and realistic embellishments); backsliding (it’s often tempting and safe to agree with a stated or implied ‘but’, or a fact that seemingly raises obstacles, and hence move towards a Less-Than-Best Possible Outcome); deference to power (agreeing with the person with the most power, no matter how accurate, valuable, or helpful their comment may be); cultural resistance (in some cultures it’s unacceptable to admit weakness or doubt, or to advance unorthodox ideas); and jumping to conclusions (some participants getting impatient and trying to move to action at a perceived “good enough” stage, before the group has completed the process).

This process of story creation is a natural one, but it needs to be skilfully managed. Participants need to be coached to avoid trying to convince others of the validity of what they’re saying, and instead let the story emerge freely. Others cannot be allowed to butt in out of turn with “related ideas”, or challenging questions — power imbalances, even if they’re exercised tacitly, need to be identified and compensated for. Equal airtime must be encouraged and when necessary enforced. In that sense this process follows some of the strictures of Bohm Dialogue and other free-flow dialectic processes.

When the process or the story runs into doubts and “buts”, the facilitator needs to step in to put the process back on its tracks and get the group to persevere and “trust the process”.

Once the story has reached consensus, it’s then up to the facilitator to re-sequence it more coherently, but without paraphrasing, embellishing or eliminating anything that’s been said: It must remain the group’s story in the group’s own words.

One of the things I’m coming to appreciate is that, while we may have no “free will” (we’re going to say and do what we were going to say and do anyway, given our conditioning and the specific circumstances of the moment), our conditioning is affected by others’ conditioning. That’s why, properly facilitated, this collective process not only can produce clarity and momentum on the Best Possible Outcome (as perceived collectively by the group), you might say it will inevitably do so, better than any set of individual thinking and imagining, and better than any less smartly facilitated process, would do.

There are of course more steps to this, to bring the envisioned Best Possible Outcome to fruition. One of them I particularly like is engaging the group to each identify which aspects of the realization of the Best Possible Outcome they are particularly inspired to be involved with — a Follow the Energy approach.

I’ve already applied this to a couple of personal and group situations I’ve been involved with, so I can vouch for it, and have added it to my “toolkit” of methods and techniques I find highly useful, especially in group activities — methods like Open Space, Appreciative Inquiry, and Circle.

It seems to me that this Best Possible Outcome method can be effectively applied in many different contexts. You can use it personally to “get over” anxieties that a situation has brought up for you that might be paralyzing you. You can use it when a group gets bogged down in negative thinking and productive debate. You can use it to gently correct an ill-advised and uninformed management directive. You can use it with a group who don’t know each other to tackle urgent or “wicked” problems and predicaments that will never have an obvious or complete analytically-determinable solution.

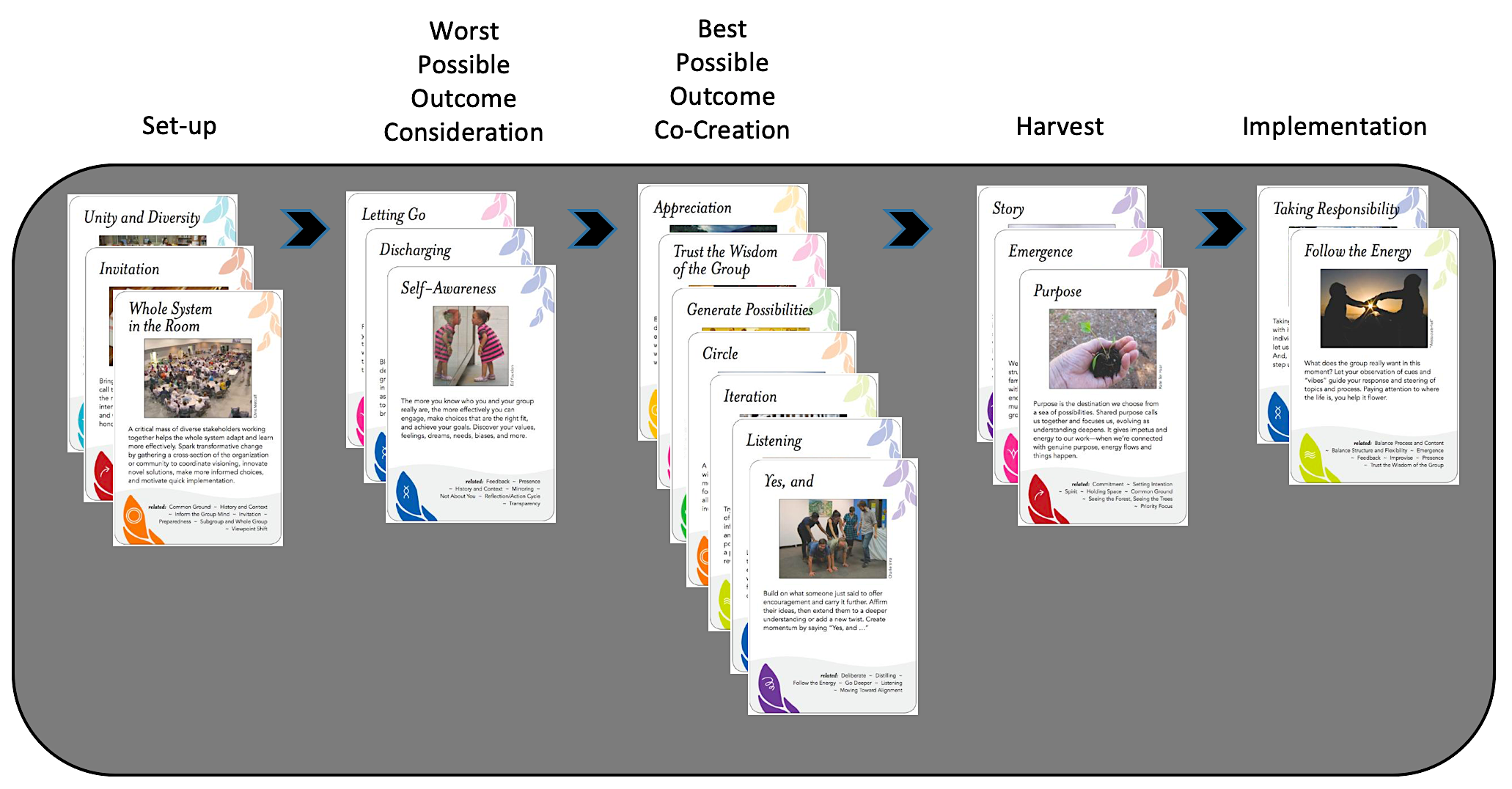

I’ve used the Group Works pattern language deck to “map” what I think are the most significant group process patterns likely to be invoked with the Best Possible Outcome method. You can see the map at the top of this post.

I think it’s a compelling approach, and one I want to explore more. As a self-described “joyful pessimist” I have a propensity to be uselessly anxious and to jump quickly to Worst Possible Outcome thinking. So this might not only be effective when I’m dealing with group challenges, it might be personally therapeutic as well.